I’ve been drawn back to this BBC warhorse for many a year now. Most often, the eight records constitute benign interruptions within a rambling biography of the guest. So rare and precious are those occasions when the records seem to stand for constituent pieces of that human’s soul. On that basis, I’ve made choices that I hope would outshine any biographical ramblings. I’m not terribly interested in writing my biography; still less is the public in reading it. But combine all the pieces – with their bizarre voices, their baroque theatricality, their deep vein of harmless melancholy – and there you have me, in inchoate musical form. When the BBC finally invites me over, I will no doubt be venerable, grey-haired, and fixed on markedly different choices. But I like to think a few of the below would make it.

Anthony Newley’s ‘The Man Who Makes You Laugh’ – Each us who loves Newley carries our own version of him. Here’s mine: a Newley of grandstanding showmanship and big-hearted schmaltz, forever prone to unsparing confessionals. In this song, Newley mixes some very disjointed showbiz images – circus, stand-up, vaudeville – as a channel for his abiding self-pity. I’m sure it’s unlistenable for some. But once you reach an accommodation with Newley, even his self-pity becomes rousingly cathartic, generously human. Key to navigating Newley is getting to know his unique voice, that caramel discharge of rumbling, reverberant emotion. The climaxes of ‘The Fool Who Dared to Dream’ (robust vibrato) and ‘I’ll Begin Again’ (a more aged, tremulous vibrato) are exemplars of where the Newley voice could go – and each is, for me, perfect in its imperfection. Newley’s vibrato has sometimes reduced me to tears. This time, Newley translates his talent for building to these devastating climaxes into a different form: a short story that runs down musical tracks. I’ve previously written on ‘The Man Who Makes You Laugh’ at length: by all means have a look. The song is a balm for any and all disaffected entertainers; and should I ever acquire a singing voice, I damn well want it to be Newley’s.

Anthony Newley’s ‘The Man Who Makes You Laugh’ – Each us who loves Newley carries our own version of him. Here’s mine: a Newley of grandstanding showmanship and big-hearted schmaltz, forever prone to unsparing confessionals. In this song, Newley mixes some very disjointed showbiz images – circus, stand-up, vaudeville – as a channel for his abiding self-pity. I’m sure it’s unlistenable for some. But once you reach an accommodation with Newley, even his self-pity becomes rousingly cathartic, generously human. Key to navigating Newley is getting to know his unique voice, that caramel discharge of rumbling, reverberant emotion. The climaxes of ‘The Fool Who Dared to Dream’ (robust vibrato) and ‘I’ll Begin Again’ (a more aged, tremulous vibrato) are exemplars of where the Newley voice could go – and each is, for me, perfect in its imperfection. Newley’s vibrato has sometimes reduced me to tears. This time, Newley translates his talent for building to these devastating climaxes into a different form: a short story that runs down musical tracks. I’ve previously written on ‘The Man Who Makes You Laugh’ at length: by all means have a look. The song is a balm for any and all disaffected entertainers; and should I ever acquire a singing voice, I damn well want it to be Newley’s.

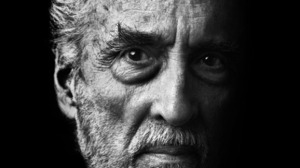

James Bernard’s ‘The Victory of Love’ from Taste the Blood of Dracula – For its acolytes, Hammer Films represents a distinct world, one that might as well exist. There is its surface terrain of quaint inns, drawing rooms and churches in muted shades – which then explode with the high-coloured, galvanic demonism of Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. It’s close to a surrogate religion – the imagined other world, the heaven-and-hell divide – which might be why this Bernard piece works on me so. It closes the film, just after Lee’s Dracula suffers his fourth ignoble destruction (he had three still to come). The strings build up, up, up – seemingly to the heavens – before their release in the love theme from the film’s beginning. And all within the confines of the village church. There’s a persuasive argument that the Gothic Revival was built on a superficial (and often camp) regard for high church trappings; thus the tricksy medievalism of The Castle of Otranto. Bernard accomplishes this for me in musical terms. His yearning strings reminds me how transporting the trappings of faith can be, if not the substance. I would make for a first-class lapsed Catholic. For me, Bernard’s other most evocative themes are the main titles for The Curse of Frankenstein and, especially, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (the film that inducted me to Hammer). All prove that so-called horror films can be breathtakingly beautiful.

James Bernard’s ‘The Victory of Love’ from Taste the Blood of Dracula – For its acolytes, Hammer Films represents a distinct world, one that might as well exist. There is its surface terrain of quaint inns, drawing rooms and churches in muted shades – which then explode with the high-coloured, galvanic demonism of Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. It’s close to a surrogate religion – the imagined other world, the heaven-and-hell divide – which might be why this Bernard piece works on me so. It closes the film, just after Lee’s Dracula suffers his fourth ignoble destruction (he had three still to come). The strings build up, up, up – seemingly to the heavens – before their release in the love theme from the film’s beginning. And all within the confines of the village church. There’s a persuasive argument that the Gothic Revival was built on a superficial (and often camp) regard for high church trappings; thus the tricksy medievalism of The Castle of Otranto. Bernard accomplishes this for me in musical terms. His yearning strings reminds me how transporting the trappings of faith can be, if not the substance. I would make for a first-class lapsed Catholic. For me, Bernard’s other most evocative themes are the main titles for The Curse of Frankenstein and, especially, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (the film that inducted me to Hammer). All prove that so-called horror films can be breathtakingly beautiful.

Regina Spektor’s ‘Samson’ – This song is a melancholy prism. It speaks to me of people I love (it was recommended me by a close friend); it reminds of people I used to love (the line ‘your hair was long when we first met’ carries me right back to scenes at university); and it reminds me of people I’ve loved but lost (Samson’s long hair has fallen away; it is a song of cancer as much as myth). ‘My sweetest downfall’ is a brilliantly economical way of expressing how we’re at once destroyed and created in opening ourselves up to other people. Kindness and acceptance will leave us as quivering and vulnerable as any cruelty. Spektor has a wonderfully haunting voice. It’s a little tarnished, cracked, smokey; a fine crystal tumbler filled with clouded water. As with Newley, any quirks of sound production are less mannerism than idiosyncratic sincerity. The piano anyway gives that quirkiness a stabilising background.

Regina Spektor’s ‘Samson’ – This song is a melancholy prism. It speaks to me of people I love (it was recommended me by a close friend); it reminds of people I used to love (the line ‘your hair was long when we first met’ carries me right back to scenes at university); and it reminds me of people I’ve loved but lost (Samson’s long hair has fallen away; it is a song of cancer as much as myth). ‘My sweetest downfall’ is a brilliantly economical way of expressing how we’re at once destroyed and created in opening ourselves up to other people. Kindness and acceptance will leave us as quivering and vulnerable as any cruelty. Spektor has a wonderfully haunting voice. It’s a little tarnished, cracked, smokey; a fine crystal tumbler filled with clouded water. As with Newley, any quirks of sound production are less mannerism than idiosyncratic sincerity. The piano anyway gives that quirkiness a stabilising background.

Franz Waxman’s ‘The Creation’ from Bride of Frankenstein – I’m no longer sure that this is my favourite horror film. But it’s certainly one that I can’t do without. This piece is straightforwardly thrilling, scoring as it does the ‘birthing’ of the monster’s mate. The pulsing drum mimics her beating heart, which Frankenstein has in his laboratory. There’s a primal excitement to that; a womb-like imperative to gather life from the rhythm. But the keynote is anarchy. James Bernard’s scores are the Gothic distilled. Franz Waxman is happier to subvert, turning his ‘Creation’ into a melting pot of widespread cultural influences. There are dissonant flashes that remind me of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring; alarming creaks that put me in mind of that Looney Tunes stock piece ‘Powerhouse’; and a decadent, intoxicating glamour that reminds me that this heady perversity emanated from Golden Age Hollywood. The unforgettable theremin looks ahead to 1950s sci-fi, not to mention ‘Bali Hai’ from the musical South Pacific. It reminds me of the diverse reasons I fell in love with vintage horror films. And makes me question why I devote my time to anything else.

Franz Waxman’s ‘The Creation’ from Bride of Frankenstein – I’m no longer sure that this is my favourite horror film. But it’s certainly one that I can’t do without. This piece is straightforwardly thrilling, scoring as it does the ‘birthing’ of the monster’s mate. The pulsing drum mimics her beating heart, which Frankenstein has in his laboratory. There’s a primal excitement to that; a womb-like imperative to gather life from the rhythm. But the keynote is anarchy. James Bernard’s scores are the Gothic distilled. Franz Waxman is happier to subvert, turning his ‘Creation’ into a melting pot of widespread cultural influences. There are dissonant flashes that remind me of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring; alarming creaks that put me in mind of that Looney Tunes stock piece ‘Powerhouse’; and a decadent, intoxicating glamour that reminds me that this heady perversity emanated from Golden Age Hollywood. The unforgettable theremin looks ahead to 1950s sci-fi, not to mention ‘Bali Hai’ from the musical South Pacific. It reminds me of the diverse reasons I fell in love with vintage horror films. And makes me question why I devote my time to anything else.

Stephen Sondheim’s ‘Giants in the Sky’ from Into the Woods – My favourite of all of Sondheim’s songs – although it has stiff competiton from ‘Move On’, ‘I’m Still Here’ and ‘Not a Day Goes By’. Funny, actually, how all of these titles have a spatial dimension. ‘Giants in the Sky’ harnesses space with innocence and awesomeness both: locating the imagination way, way up in the clouds. It transports me back to the fairytales of early childhood, when the likes of Disney’s (grippingly macabre) Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs constituted my whole imaginative universe. I love the child-like boldness of expression: the heaping-on of adjectives in ‘big, tall, terrible’ is genius, as are the breathtaking exclamations of ‘not till the sky!’ and ‘after the sky!’. Throughout is a note of nagging yet gentle acceptance – something I’d argue as the most painful but necessary of emotional rites. I stumbled on this song just before leaving university, in the bittersweet twilight between last exams and graduation. These words in particular rang out: ‘And you’re back again only different than before’. My Sondheimian runner-up would be ‘Loving You’ from Passion, which follows acceptance into the darker territory of emotional martyrdom.

Stephen Sondheim’s ‘Giants in the Sky’ from Into the Woods – My favourite of all of Sondheim’s songs – although it has stiff competiton from ‘Move On’, ‘I’m Still Here’ and ‘Not a Day Goes By’. Funny, actually, how all of these titles have a spatial dimension. ‘Giants in the Sky’ harnesses space with innocence and awesomeness both: locating the imagination way, way up in the clouds. It transports me back to the fairytales of early childhood, when the likes of Disney’s (grippingly macabre) Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs constituted my whole imaginative universe. I love the child-like boldness of expression: the heaping-on of adjectives in ‘big, tall, terrible’ is genius, as are the breathtaking exclamations of ‘not till the sky!’ and ‘after the sky!’. Throughout is a note of nagging yet gentle acceptance – something I’d argue as the most painful but necessary of emotional rites. I stumbled on this song just before leaving university, in the bittersweet twilight between last exams and graduation. These words in particular rang out: ‘And you’re back again only different than before’. My Sondheimian runner-up would be ‘Loving You’ from Passion, which follows acceptance into the darker territory of emotional martyrdom.

Damien Rice’s ‘Dogs’ – A puzzle to be solved on each hearing. Thanks to its striking images, lightly (and ambiguously) worn, the song encourages a meditative state, a heightened concentration. Aside from that, it’s very pleasing to the ear. Playful lyrics, full always of circling, child-like motion; I’m particularly fond of ‘we drive around and she drives us wild’. The gentle tweakings of the acoustic guitar. Rice’s voice, soulful almost to androgyny. There’s also a structural reason to like it: on Rice’s album 9, ‘Dogs’ comes directly after ‘Rootless Tree’. Which is deadeningly bleak. It is therefore like the sun coming out – just as in Fantasia, where ‘Ave Maria’ follows ‘A Night on Bald Mountain’. A phoenix from the ashes. It’s given me hope in darker periods. This hope is so much more precious for being hard-won; equally precious are Rice’s other brighter spots, in the likes of ‘Older Chests’ and (more arguably) ‘Colour Me In’. Rice seems to average one fit of optimism per album. ‘Dogs’ is a modern transposition of the sun-dappled, life-giving finales of Dickens’ greatest novels. We know that despair and death are real, but we are content, for the present, to bask in the sun.

Damien Rice’s ‘Dogs’ – A puzzle to be solved on each hearing. Thanks to its striking images, lightly (and ambiguously) worn, the song encourages a meditative state, a heightened concentration. Aside from that, it’s very pleasing to the ear. Playful lyrics, full always of circling, child-like motion; I’m particularly fond of ‘we drive around and she drives us wild’. The gentle tweakings of the acoustic guitar. Rice’s voice, soulful almost to androgyny. There’s also a structural reason to like it: on Rice’s album 9, ‘Dogs’ comes directly after ‘Rootless Tree’. Which is deadeningly bleak. It is therefore like the sun coming out – just as in Fantasia, where ‘Ave Maria’ follows ‘A Night on Bald Mountain’. A phoenix from the ashes. It’s given me hope in darker periods. This hope is so much more precious for being hard-won; equally precious are Rice’s other brighter spots, in the likes of ‘Older Chests’ and (more arguably) ‘Colour Me In’. Rice seems to average one fit of optimism per album. ‘Dogs’ is a modern transposition of the sun-dappled, life-giving finales of Dickens’ greatest novels. We know that despair and death are real, but we are content, for the present, to bask in the sun.

Tony Jay’s ‘Hellfire’ from The Hunchback of Notre Dame – It’s been ten years since Tony Jay left this planet. He took with him my all-time favourite voice. In many respects, it’s a peculiarly constrained voice: the thickened diction, the narrow range, a timbre alternately bone-dry and clammy as the tomb. But it carries with it an outsize, all-pervading Gothic atmosphere, ideally suited for Victor Hugo. ‘Hellfire’ puts Jay’s voice through its paces – composer Alan Menken was determined that Jay sing it just slightly beyond his comfortable vocal range. Jay’s voice is also a magnificent throwback: within it, I divine traces of George Zucco and Henry Daniell, to name but two. Underrated character actors, much like Jay himself. But all have found an immortality in the cinema. Tony Jay bears much responsibility for getting me interested in acting (I saw the Hunchback a good six or seven years before Lon Chaney sealed my fate). Quite apart from Jay’s contribution, the song is laudably audacious. Its central ‘hellfire’ refrain, amplified by the choir, transposes ‘The Bells of Notre Dame’ to a minor key. Thus, one can take the villain song as the film’s dark heart. It has always seemed so to me. I’ve written on ‘Hellfire’ in a wider context here.

Tony Jay’s ‘Hellfire’ from The Hunchback of Notre Dame – It’s been ten years since Tony Jay left this planet. He took with him my all-time favourite voice. In many respects, it’s a peculiarly constrained voice: the thickened diction, the narrow range, a timbre alternately bone-dry and clammy as the tomb. But it carries with it an outsize, all-pervading Gothic atmosphere, ideally suited for Victor Hugo. ‘Hellfire’ puts Jay’s voice through its paces – composer Alan Menken was determined that Jay sing it just slightly beyond his comfortable vocal range. Jay’s voice is also a magnificent throwback: within it, I divine traces of George Zucco and Henry Daniell, to name but two. Underrated character actors, much like Jay himself. But all have found an immortality in the cinema. Tony Jay bears much responsibility for getting me interested in acting (I saw the Hunchback a good six or seven years before Lon Chaney sealed my fate). Quite apart from Jay’s contribution, the song is laudably audacious. Its central ‘hellfire’ refrain, amplified by the choir, transposes ‘The Bells of Notre Dame’ to a minor key. Thus, one can take the villain song as the film’s dark heart. It has always seemed so to me. I’ve written on ‘Hellfire’ in a wider context here.

John Du Prez’s ‘Finale’ from A Fish Called Wanda – This piece I find purely and ecstatically joyful. Precisely why is a bit elusive. I’ve a degree of affection for the film, particularly its depiction of a beautiful eighties London (it holds a certain romance for those of us lucky enough to not actually have been there). Yet I’ve never found it as funny as John Cleese’s other works. I do vibrate to the saxophone – the end of ‘Old and Wise’ by The Alan Parsons Project, for instance, and Lisa’s immortal ‘Jazz Man’ from The Simpsons. As with ‘Dogs’, there’s the beauty of the acoustic guitar. Perhaps all that’s enough. But let’s chalk it up to a choice intersection of music and moment. I recall being drawn to the film, aged thirteen or fourteen, because Stephen Fry has an incredibly brief cameo. Fry was a figure who gave me a certain hope about my (then dread-inducing) future as a gay man. The likes of Wilde, Williams, Crisp and Callow were to follow and eventually usurp him. It’s that long-ago spark which imbues it with hope for me. Along with Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique (the third movement, specifically), it might be my gay anthem.

John Du Prez’s ‘Finale’ from A Fish Called Wanda – This piece I find purely and ecstatically joyful. Precisely why is a bit elusive. I’ve a degree of affection for the film, particularly its depiction of a beautiful eighties London (it holds a certain romance for those of us lucky enough to not actually have been there). Yet I’ve never found it as funny as John Cleese’s other works. I do vibrate to the saxophone – the end of ‘Old and Wise’ by The Alan Parsons Project, for instance, and Lisa’s immortal ‘Jazz Man’ from The Simpsons. As with ‘Dogs’, there’s the beauty of the acoustic guitar. Perhaps all that’s enough. But let’s chalk it up to a choice intersection of music and moment. I recall being drawn to the film, aged thirteen or fourteen, because Stephen Fry has an incredibly brief cameo. Fry was a figure who gave me a certain hope about my (then dread-inducing) future as a gay man. The likes of Wilde, Williams, Crisp and Callow were to follow and eventually usurp him. It’s that long-ago spark which imbues it with hope for me. Along with Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique (the third movement, specifically), it might be my gay anthem.