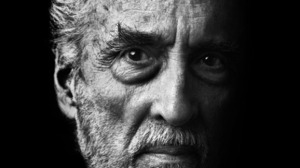

Most of my heroes in acting are long dead. Karloff, Wolfit, Irving – there’s no need for me to come to terms with their absence. I have known them always as completed by death: their narratives lying fully writ. So it was a considerable shock to me when Christopher Lee passed away. A full acceptance isn’t possible when you’ve gotten used to someone’s life and work developing before your eyes. Even now I feel cheated of closure. As I prepared to play Frankenstein’s Creature – Lee’s breakthrough role, back in 1957 – I started to meditate on the great man’s legacy.

Christopher Lee remains a mystery to me. For over half my life, family and friends have brought me his newspaper clippings; warned me of his television appearances; accompanied me to Tim Burton films, just to hear his two or three fateful utterances. And yet I can explain practically nothing about Lee – neither the actor, the man, nor the uncanny filmic hinterland where the two fused as one.

Lee’s life reads to me like an old mystery play: a profound and dazzling romance, founded throughout on the supernatural. And as with the mysteries, there is a return from the dead. Taken collectively, Lee’s performances as Dracula constitute a dark parody of the Christian Resurrection. His Stations of the Cross are frenziedly theological; particularly Christ-like are his impalements on a giant crucifix and, a century later, on a hawthorn hedge. A principal delight of the Hammer series was in witnessing how each successive film – with varying results – undid the death in its predecessor. Now death has come for real – but the romance is still hanging in the air.

For it has been a romance. Albeit one conducted mostly within my head, across many years of prizing up the holy relics. Such has also been my experience with Lee’s compatriots in terror cinema: with Lon Chaney; with Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff; with Vincent Price and Peter Cushing. Only Christopher Lee was very much alive and, until recently, very active. Primary contact is lost in the fog of early childhood, though it was probably his King Haggard in The Last Unicorn. My first really conscious inheritance was Lee’s Saruman in The Fellowship of the Ring. Captive in the cinema, aged only ten, I awakened to the beauty of that smouldering voice:

Smoke rises from the Mountain of Doom. The hour grows late, and Gandalf the Grey rides to Isengard, seeking my counsel. For that is why you have come – is it not? My old friend…

Old friend indeed. For somehow, strangely, I had intimated that this was Christopher Lee whilst watching him. It was something in the long, angular hands, in the dark Italian skin and the noble features (albeit compressed by a false nose). A dormant memory, perhaps. I had previously been fascinated by a photo of Lee’s Dracula in the Osborne Book of the Haunted World: spattering blood over Melissa Stribling’s throat, a long hand hovering suggestively close. I put Dracula aside for a time, and applied myself to impersonating Saruman on the secondary school field. Striving (ever vainly) to channel Lee’s voice became one of my first experiments in acting.

I first came to Hammer with Dracula Has Risen from the Grave. A pan-and-scan viewing on grungy VHS, recorded by my dad in the early hours. Yet the film still bled its autumnal colours upon its heaps of Catholic iconography – the candlesticks, the prayer-books, the vestments, the crosses – with all heightened into ritual by James Bernard’s funereal score. At the centre was Lee’s majestic Count Dracula, backed by infernal red sunsets, never more picturesque. I soon saw Dracula: Prince of Darkness – courtesy of my grandma, another late-night VHS – in which Lee’s wordless vampire became a solely picturesque entity. Then, aged just twelve, I gained the unholy trinity. Lee’s founding Hammer monsters: in The Mummy, in the original Dracula – and in The Curse of Frankenstein, which for a while was my favourite of all of them.

Lee’s Creature is the jagged heart of this elegantly brutal film. It remains a spectacularly underrated performance – because, as ever, Lee operates by stealth. Not that his Creature lacks for visceral impact; The Curse of Frankenstein is a powerful reminder that, for a decade at least, Lee was regarded as the most frightening actor in the world. There is the scene of the Creature’s first unveiling. Lee is revealed standing in the laboratory, swathed entirely in dripping bandages. He then tears them away to reveal his horrendously scarred head, the camera barrelling in for an overwhelming screen-filling close-up. A dead eye, decayed teeth, that blotchy, corpse-like skin. In 1957, the effect must have been paralysing.

Lee’s Creature is cemented as destructive juggernaut when he encounters a blind man in the forest. This Creature struggles to comprehend, misinterprets, then brutally murders the man (and, we are led to believe, his grandson). It’s a pitiless rewriting of the most sentimental passage in Mary Shelley’s novel, not to mention Universal’s Bride of Frankenstein. Karloff’s Monster seemed always to be a gentle, soulful being: the Hollywood equivalent of the noble savage, an impression augmented by a clean, streamlined makeup. Lee’s Creature hasn’t a hope in hell. He’s an abortive, soulless automaton, with a cut-and-paste visage to match (as one critic put it: ‘a road accident’). To watch him is acutely painful, like watching a brain-damaged animal that must be put out of its misery.

Yet there’s much more at play in Lee’s Creature. Very few actors can make you believe in the supernatural as Lee did. Paul Scofield was one. When Scofield, as the Ghost in Hamlet, says ‘I am thy father’s spirit’, you believe him. When Lee plays Dracula – with deadly sincerity, in the direst of films – you believe him too. There are other connections with Scofield: the regal bearing, the resonant voice, the Italian appearance, that haughty demeanour punctuated by unexpected impishness. Nor was either actor particularly ostentatious, despite roles that offered countless opportunities for extravagance.

The significant difference is that Scofield was regarded as legitimate, by virtue of his work in the fashionable theatre. Lee was not. Like Henry Irving, his Gothic-knight precursor, Lee stood for the Gothic. But unlike Irving, Lee belonged to an age when the Gothic was afforded little respect. It is sad that Lee’s imaginative achievements have therefore been downgraded. Scofield could afford to refuse a knighthood (and so he did, several times). Lee owed it to the Gothic to accept.

As with Scofield, there remains something fundamentally unknowable about Lee. Neither man ever discussed acting in any depth. Lee’s memoirs, whilst detailed, contain scant clues about his process. When pressed, Lee might quote Ralph Richardson on acting as ‘dreaming to order’. But he seldom went further. It’s tempting to say that Lee couldn’t go further. Much like Richardson, Lee cultivated (perhaps unintentionally) an image as a cantankerous old dinosaur, all no-nonsense blustering and portentous secret-keeping. Such was the sustaining joy of his late-career interviews. And such a man is not to be asked his opinion on the artistic process.

In his approach to acting, then, Lee might well have been a mystic. It is perhaps the only way that such a man can be an actor. I think of the great mantra of Claude Rains, another of these invisible actors: ‘I learn the lines and pray to God’. It’s an excellent summation of a process that remains thoroughly mysterious. As far as Lee was concerned, there was nothing to be discussed.

These are thrilling grounds on which to engage with Lee’s performances: as dreams, quite unreadable. The earliest Gothic fictions were derived from dreams. So were the first Gothic films. This is confirmed by a glance at The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a film compounded of such stuff as dreams are made on. Here we find the template for Lee’s Creature: in Conrad Veidt, who was Lee’s great acting hero. Veidt’s Somnambulist shares much with Lee’s Creature: the juddering, puppet-like movements; the light-sucking black garments; the gawkily expressive hands. Above all, there is the fascinating spectacle of a beautiful man giving his all to remould himself as grotesque.

Lee can’t have been oblivious (or unreceptive) to these parallels with Veidt. Emulation is vital to an actor’s early development. But in later life, Lee seemed to become his own strange creation. Here the mystery only deepens. For we can study Lee’s transformation, preserved on film across his incredibly long-drawn career; a nearly seventy-year journey from clean-cut youth to bearded magus. Perhaps only Angela Lansbury affords a more sustained view of an actor’s development. Yet her transformation has been nothing compared to Lee’s.

The most intriguing physical specific is Lee’s toupée. To keep knowledge of it from the public, Lee gave it an inconsistent mythology. At times, he claimed to have shaved his head for The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes; at others, to have worn a bald-cap. When filming The Mummy, Lee apparently refused to remove his toupée, subjecting it instead to his heaviest makeup. There is also the matter of Lee’s changing voice. Robert Quarry avowed that the famous ‘Christopher Lee voice’ was a rank affectation, a put-on. Quarry was a weirdly hostile co-star; yet there’s also that celebrated outtake from The Fellowship of the Ring (‘I cannot get up these goddamn steps smoothly!’), where Lee, caught off guard, speaks in a higher register than his tightly-clamped bass. Although voices change with age, Lee seems to have cultivated his. It’s disarming how unlike himself Lee sounds in the 1958 Dracula. But ten years on, in Dracula Has Risen From the Grave, the stentorian growl of Saruman is creeping in. With time, Lee became exactly what he pretended to be. A lesson for all actors.

In his recent tribute, Ian McKellen described Lee’s Saruman as possessing ‘the air of a stern yet benign Pope’ with hidden reserves of ‘cruelty and spite’. Perhaps Lee’s greatest gift was in revealing where the sacred and the profane came together. It’s naturally central to the Frankenstein myth: the sanctity of God-created life versus the blasphemy of the devilish Creature. Lee’s Jekyll-and-Hyde embodiment in I, Monster was also sensitive and engaging. But there are yet more daring examples. His Lord Summerisle in The Wicker Man is a man who sacrifices with a disarming smile. His performance as Rasputin: The Mad Monk contains many potent moments, distilled in some mesmerising speeches:

During the time that I’ve been here, you’ve tried to teach me that confession of my sins is good for the soul. You also removed all temptation from among us so that there’s no chance of any sin here. I merely tried to put that right. When I go to confession, I don’t offer God small sins, petty squabbles, jealousies. I offer him sins worth forgiving.

Whenever Lee played the monster hunter – in The Gorgon, or The Devil Rides Out, or Horror Express – he cut a figure almost as forbidding as the monsters themselves. Ultimately, Saruman resides on the same continuum as Count Dracula: evil fused with a sense of religious ritual. Flowing, lustrous garments. Precise and commanding gestures. A terrain half-castle and half-church. And above all, that sense of authenticity – that belief which Lee brought to everything he played, whether Stoker’s gaslight melodrama or Tolkien’s Black Speech.

So formidably dour was Lee’s persona that it’s easy to overlook the raw humanity in his best performances. In 2011, the fabled Japanese reels for Dracula were found – and it was discovered that Lee’s Dracula cries human tears. Astonishingly brave, astonishingly unexpected (Lee’s constant creed in acting), and more effortlessly poignant than anything in Gary Oldman’s overblown opus. Lee held fast to his mystery, though, and kept the front up in public.

In this way, Lee stood apart from his terror contemporaries. Vincent Price was so amiably dedicated to promoting the arts that he seemed eminently approachable. Peter Cushing’s sorrow at his wife’s passing was deeply humanising, and a comfort to many. Lee, by comparison, came across as rather cold. It wasn’t so. Those who saw the mask drop at the BAFTAs knew it. The behind-the scenes footage from Flesh and Blood is also heart-warming, Lee swapping Looney Tunes gifts and voices with Peter Cushing. Lee’s reminiscences about the long-lost Cushing and Price were never less than moving. It’s certainly the highlight of his revised memoirs, this sense of Lee communing with absent friends. We horror fans live vicariously through the emotional lives of its stars. It’s a comfort to know that Dracula cries; that he might even cry for a friend. It places a beating heart within the Gothic skeleton. On receiving his knighthood in 2009, Lee privately remarked that the honour was meant for Cushing.

My years spent with Lee come back to me in a haze now. I was disheartened when he was cut from The Return of the King; I was thrilled when he was impersonated by Stephen Fry on QI (Fry was then another really formative influence). I looked forward to dissecting Lee’s bewildering Christmas Messages, those increasingly free-form capsules of mortality. I was even a patron of Lee’s widely reviled singing career. In my first year at Cambridge, I fell in love whilst listening to Lee’s intoxicating ‘Name Your Poison’ from The Return of Captain Invincible. A few weeks later, I found cassettes of Lee reading Peter and the Wolf and The Soldier’s Tale in a charity shop, thus rounding off a very heated term. I’m listening to them now.

It’s fitting that my last sighting of Lee was in the cinema where I’d seen The Fellowship of the Ring. Now, more than half a lifetime older, I bore witness to the credits of the final Middle Earth film. There again was Saruman – just as I’d seen him first – now an etching, fading to white, to the elegiac accompaniment of ‘The Last Goodbye’.

Only it isn’t goodbye. Closure isn’t necessary. Not just yet. As long as there are still films of his that I haven’t seen – and there are well over a hundred – then that last goodbye need not come. Christopher Lee was a part of my development, my self-creation. And I am certain his legacy, however mysterious, will continue to shape my life.

God preserve you, my hero. Have a ball with Peter and Vincent.